I’m a big believer in parental intuition so I’m hesitant to call any book “essential reading” for parents. That means I wouldn’t say every parent needs to drop what they’re doing and pick up a copy of The Siren’s Call by Chris Hayes. But the book does provide some great insight for parents to consider while leading their children through what can feel like the minefield of digital life.

Hayes is a longtime MSNBC news host, which provides him a unique perspective for this examination into human attention, and how media today has hijacked it. Given Hayes’ resume, it’s worth mentioning that the book isn’t political, overall. There are portions where Hayes can’t seem to help himself as he veers off on small rants that you’ll love or hate, depending on your political views.

But, fortunately, those political tangents don’t take up too much of the book because the core ideas he shares are both non-partisan and insightful. As a parent, I’m definitely glad I read it.

Let’s take a look at the three biggest ideas, and how they can be useful to parents today.

The Value of Attention

Early in the book, Hayes makes an argument that is both foundational for the rest of the book and had my wheels spinning for days. He writes:

“Attention is the substance of life.”

Put another way, your life is the sum total of everything you pay attention to. Obviously, this puts a big premium on attention.

On the micro level it suggests we each ought to be very intentional about what we choose to pay attention to, and careful to guard against things trying to grab our attention. On the macro level, it suggests that attention can be viewed as a type of resource. And like other resources — such as oil or gold — it can be extracted. Extracted for what purpose? The same reason other resources are extracted: to make money and gain power. In Hayes’ words:

“Attention [has] value and if you can seize it you seize that value.… Those who successfully extract it command fortunes, win elections, and topple regimes…. Every single aspect of human life across the broadest categories of human organization is being reoriented around the pursuit of attention.”

In contrast to information, attention is finite. It is scarce. And scarcity drives up value. Hayes spends most of the book explaining the implications of this today but, to fully understand that discussion, you need to understand that there are different types of attention. So let’s look at those first.

Three Types of Attention

Hayes argues that there are three distinct types of attention:

- Voluntary attention

- Involuntary attention

- Social attention

The first two are fairly obvious and easy to grasp: voluntary (what we choose to pay attention to) and involuntary (what we pay attention to without conscious effort). The third, social attention, is a little more complicated. Hayes uses a simple metaphor that’s useful for understanding the interaction of these three types.

Imagine you’re at a cocktail party having a discussion with a new acquaintance who is telling you about what she does for a living. As you listen, you’re exhibiting voluntary attention. Even though there are other things in the room vying for your attention — other conversations being had, waiters moving around with trays of food — you’re able to keep your attention fixed on what she is saying because like all humans you’ve inherited some pretty good psychological defenses that allow you to block out distractions.

But then across the room a waiter drops a tray of glasses and they shatter all over the ground. Suddenly, without any conscious decision-making going on, you turn to look at the source of the noise. Everyone else in the room does too. This is involuntary attention. It is also an evolutionary adaptation born from the need to survive — to avoid the predator lurking in the nearby brush, to move out of the way when something big comes crashing down, etc.

You might think of these two types in terms of grabbing attention (involuntary) and keeping attention (voluntary). It’s relatively easy to grab attention — anyone of us could singlehandedly turn all the heads at the party by standing on a table and shouting or walking through the room naked. It’s relatively hard to keep attention — few of us could singlehandedly keep that same room full of people entertained for a full hour.

To understand social attention, return to the hypothetical conversation where you’re talking to the acquaintance about what she does for a living. What she’s saying is interesting so you’re fully engaged. But, while she’s talking, you overhear your name said in a nearby conversation. Even if it’s not said loudly, urgently, or in any other remarkable way, it’s going to grab your attention.

Hayes sums it up this way:

“We are creatures that pay attention to things in our environment, yes, but also to other people. In turn we seek their attention on us. There is a reason it is our name, and not some other keyword, that wrenches our attention toward that overheard conversation: We want to know who’s talking about us. Who is paying attention to us. And this social need will always be a central aspect of the complex frictions at work in how our own attention is focused. In fact, it is this facet of attention that the attention merchants of the age have most effectively exploited.”

What’s Happening to Attention Today

I’m sure you’ve heard reports decrying smartphones and social media for reducing attention spans today. The evidence is real, and it is concerning, but Hayes argues that the implications are far more profound than just shrinking attention spans:

“What I want to argue here is that the scale of transformation we’re experiencing is far more vast and more intimate than even the most panicked critics have understood.…. My contention is that the defining feature of this age is that the most important resource — our attention — is also the very thing that makes us human. Unlike land, coal, or capital, which exist outside of us, the chief resource of this age is embedded in our psyches. Extracting it requires cracking into our minds.”

This is where Hayes’ ultimate conclusion most resembles Haidt’s in The Anxious Generation (which we reviewed last year), even though they come at it from different directions. The basic argument both share is that technology, and social media in particular, is doing much more than distracting us or instilling some bad habits. It is fundamentally transforming the experience of being human — and in a way that benefits the shareholders of a few big companies at the expense of us as individuals.

Think of a common approach to entertainment you and I experienced as teens compared to how our kids approach it through social media. Let’s say it was a Friday night and you and some friends wanted to hang out and watch something together. You probably went to the local Blockbuster, spent 10-15 minutes walking the aisles before you decided on a movie, brought it home, and popped it in the DVD player.

Even just doing that required a simple plan to begin with. Then, the DVD case told you exactly how long the movie would take to watch and everyone involved essentially signed up for that commitment: we give an hour and twenty-one minutes of our time and we get something fun in return. The point is that it was intentional and voluntary.

Contrast that with today’s all-too-common scene of teenagers spread around the living room, each staring dead-eyed at their own little screen. This wasn’t the plan. Nobody said, “hey let’s all get together and not talk to each other but instead just stare at our phones all night.”

What likely happened is that they all got together, one of them got a notification and pulled out their phone to check it, then another, then the third saw the other two on their phones and felt the need to check their own, and on down the line until each teen is immersed in whatever infinite feed signaled to them it was urgent that they look right here right now. There was no agreement made between them or with the supplier of the entertainment. No intentional exchange of attention for entertainment.

And that’s the key difference. Yes, things change and teens from every generation pay attention to different things than the generation before them. But the key distinction now, according to Hayes, is that kids today have inherited a world where they aren’t given a fair shot at choosing what they will pay attention to. Their attention is extracted from them.

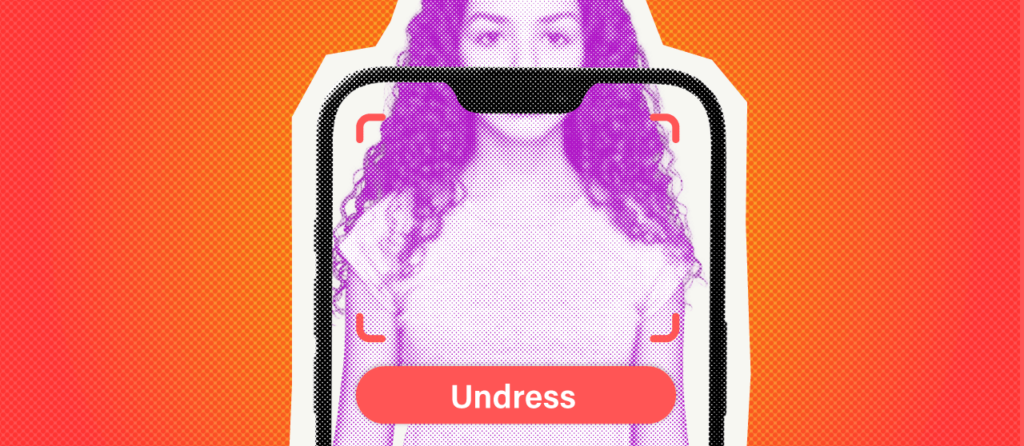

This is done by Big Tech hijacking those long-evolved aspects of human psychology: involuntary and social attention.

The social media feeds we all carry around in our pockets function effectively like a constant series of glasses smashing on the ground, constantly turning everyone’s head at the party. Or like a constant whisper in your ear of your own name, repeatedly pulling you away from anything else you might wish to focus your attention on.

This is precisely why social media is the worst offender: it layers an additional appeal to social attention on top of that sharp tug of involuntary attention. It constantly suggests that someone, somewhere is paying attention to you. Or makes you feel like they should be, but maybe aren’t.

Hayes’ point is that this is not just about losing seconds off of our attention span. This is a central aspect of our own humanity and identity being unwillfully extracted from us, second-by-second, every single day we choose to carry a smart phone around that houses these platforms. In his words, “a social system had been erected to coercively extract something from people that had previously, in a deep sense, been theirs.”

Assuming you buy Hayes’ argument, now what? What can we do in the face of this new way of life? What chance do our kids stand?

What Does This Mean for Parents?

If all of the above leaves you feeling bleak…I’m sorry. It really is kinda bleak. But I don’t believe bleak is the same as hopeless. We got ourselves into the messy state we’re in, we can get ourselves back out.

I genuinely believe there is a future where we look back at these two decades as an anomaly — not the beginning of a new way of life. Just a bad detour on our way to a world where smartphones and social media benefit individuals way more than they harm them. Here’s why.

First, our kids are a little quicker on the uptake than we were. They’re seeing the situation for what it is and they’re pushing back. Here’s a short, non-exhaustive list of movements as an example of this:

- Half the Story – Non-profit started by a teenager and focused on digital well-being that advocates for a world, “Where we, not big data, have control over our lives.”

- Ignite – Youth-led movement to “transform the way young people connect” through online resources, in-person challenges, and an app that reminds you to talk to the people you care about.

- NoSo – Short for “no social media,” this group, started by a teenager, helps schools and other groups organize month-long digital detoxes to modify the way kids interact with social media.

- ReThink – Software that detects and stops cyberbullying, created by Trisha Prabhu (when she was just 12-years-old) who has since amplified her voice as an author and public speaker.

- Young People’s Alliance – Bipartisan advocacy group started by two high school students that pushes for “taking back control of our lives” (from social media and AI, specifically).

There are plenty more out there. And that’s not to mention the countless undocumented conversations between teens who want a different relationship with technology and agree, together, to put phones down for an evening, or weekend, or more.

Second, parents are banding together — with their kids and with other parents. The whole existence of Gabb is pretty good evidence of this. The company was founded by parents who had talked to other parents and realized they weren’t the only ones who wished there were safer tech options for kids.

We’re not even a decade old but just in our lifetime as a company we’ve seen the conversation around safe tech for kids evolve from a niche concern to a common worry among parents to a mainstream issue that everyone knows about.

In 2024, we saw web traffic to our educational content (like this very article you’re reading now) more than double from the year before. Our social media followers have similarly exploded. That’s less a pat on our back and more an indication of an eruption in parental engagement with the conversation surrounding keeping kids safe online.

Like with the youth-led movements, this is also translating into great grassroots momentum — like Wait Until 8th as just one example — and an uncountable amount of person-to-person conversation around the topic. It’s making a difference. It really is.

Reason three stems from those first two: all the momentum from points one and two have created enough pressure on administrators and legislators to put pressure on Big Tech. I understand why many parents feel that this problem is too big for us to fix. Realistically, what can we do in the face of the billions of dollars worth of power these Big Tech companies wield? Honestly, a lot.

The Kids Online Safety and Privacy Act is still working its way through Washington D.C. and, as of May 2025, one report counts nearly 2,000 ongoing lawsuits involving Meta, Google, Snap, ByteDance, and other social media companies. The report also refers to this number as “the tip of the iceberg,” suggesting, “we expect many more lawsuits to get filed as more parents learn about the MDL” (multidistrict legislation).

In addition, well-publicized hearings have put Big Tech leaders in the spotlight in the worst possible way, forcing them to pledge to make changes. Some changes have already been made. Most promises still need to be fulfilled. Only time will tell if they actually do follow through in the most meaningful ways. But what we’ve seen so far isn’t nothing. Progress is being made.

How Can We Help Our Kids Today?

All of the above speaks to the collective action needed to solve this problem. And we all have a part to play in that. But if you’re like me as a parent, you’re first thought after reading a book like The Siren’s Call has more to do with what can be done by me within the walls of my own home.

Obviously, that’s your call and should be. But let me give you some ideas to consider.

- Get a handle on your own tech use: Hayes’ book does mention specific impacts on kids but, overall, his argument is aimed at all of us. If your kids watch you as you allow your phone (or other screens) to dominate your attention, it’s going to be tough to get them to listen to any tips or follow any rules you provide.

- Be deliberate about social media: If you haven’t already given your kid(s) access to their own social media accounts, make a decision on when that will happen and communicate it, along with the reasons why. This really has become a milestone decision in parenting. Don’t wait until they’re begging for it to come to a conclusion. If you’ve already given them social media and regret it, it’s not too late to change that.

- Take a tech in steps approach: Gabb was founded because parents were facing an all-or-nothing scenario when it came to smartphones. That’s not the case anymore. Take advantage of the fact that the tools now exist for you to give your child a gradual introduction to the digital world that is tailored to their personality and changing maturity level.

- Discuss this stuff often: The nature of technology is that it evolves quickly. There are no magic formulas or silver bullets I can give you to solve all your future tech-safety problems. The closest thing I can suggest is just a commitment to create a family culture where the good and bad of what’s happening online can be discussed openly. And remember, with kids, it’s usually better to listen more than you talk.

And just in case you’re feeling overwhelmed or guilty about not doing more, know this: just by being here, reading this, you’re doing the work. This is what it looks like to care and help. Keep it up.

Neglect, disinterest, and inaction are what will ensure the problems continue. None of those apply to the parent who is reading a long article about the attention economy and its impact on kids today.

Just talk to your kids about these ideas. Talk to the parents of your kid’s friends. Your sister, your co-worker, your nieces and nephews. And give yourself a break, nobody holds all this weight perfectly and nobody needs to do it perfectly. Our kids are resilient. They need our help but they don’t need perfection from us to survive and thrive in the world today.

Success!

Your comment has been submitted for review! We will notify you when it has been approved and posted!

Thank you!